Back to The Head of Orpheus: a Russell Hoban Reference Page (home).

Pilgermann here. I call myself Pilgermann, it's a convenience. What my name was when I was walking around in the shape of a man I don't know, I simply can't remember. What I am now is waves and particles, I don't need to walk around, I just go.

—Pilgermann, (p. 11—opening lines)

Pilgermann (1983)

A Novel by Russell Hoban

EDITIONS I KNOW OF:

- (UK) Hardcover (First Edition) - Jonathan Cape, Ltd. 1983.

- (US) Hardcover (First Edition) - Summit Books/Simon & Schuster, 240 pp. 1983.

- (UK) Trade Paperback - Picador (Pan Books), 1984.

- (US) Trade Paperback - Washington Square Press/Simon & Schuster, 240 pp. 1984.

- (UK) Trade Paperback - Bloomsbury, 2002.

AVAILABILITY

Pilgermann is available as part of the new Russell Hoban Omnibus from Indiana University Press. As a stand-alone it's out of print in the US, but alongside Riddley Walker it's the easiest of Mr. Hoban's books to find in a used bookstore over here. In the UK, the new Bloomsbury trade paperback edition is available at bookshops like Dillon's in London, and to the rest of the world via the Amazon UK Web site. Some used copies are generally available on the Bibliofind site.

DESCRIPTION:

It's arguable, I suppose, that you haven't really had a bad day until early one morning, fresh from an adulterous tryst with a transcendently beautiful tax-collector's wife who bears the name of wisdom, you are cornered by a Jew-hating mob in the middle of a pogrom who throw you to the cobblestones, brutally castrate you and feed your genitals to a sow. That's what happens to Pilgermann, a German Jew of the 11th century, and in the aftermath of this horrific event, he finds himself selling all of his possessions and setting off on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, at the time of the First Crusade during the years 1096 to 1098. His traveling companions include Bruder Pförtner, an acid-tongued, priapic apparition of death; the headless corpse of the tax-collector whose wife Pilgermann slept with; and the ghost of the sow who ate his "proper parts."

It sounds like a fairly dark way to get a book off the ground, and it is; but as Van Gogh once noted, the amazing thing about darkness is how much light it can contain. In this case the light comes from the luminous meditations of Pilgermann, who stands outside of time telling the tale of his journey, interweaving its events with reflections on death, time, the works of Vermeer and Bosch, the machinery of God, the dreams of popes, and the infinity revealed in geometric patterns.

His road leads eventually to the walled city of Antioch, where, at the behest of a wise and philosophically-inclined merchant named Bembel Rudzuk, he starts work on an enormous landscape of tiles arranged in a geometric pattern of his own discovery called "Hidden Lion" (seen on the book cover above left), with an observation tower in the middle.

Pilgermann is a work of remarkable depth, a difficult tour de force that leaves one feeling at once humbled and elevated by the amount of feeling and perception that informs it. It seems to me that Paul Gray, writing in Time magazine, called it exactly right when he wrote that "Pilgermann is not an easy read, only a fascinating and rewarding one." I owned this book for several years, and started it innumerable times before I finally finished it—it's a bit slow to get going, and it's easy to be disheartened by the grimness of the opening scenario, or get bogged down in some of the longer essayistic passages toward the beginning. But Mr. Hoban's forays into essay, like those of Milan Kundera, always ultimately reward the reader's patience; and if you bail out early on Pilgermann's journey, you'll miss out on the revelations that await him, and those readers stouthearted enough to stick with him.

NOTES:

In the acknowledgements at the book's beginning, Mr. Hoban tells us that Pilgermann is a sort of sequel-in-spirit to Riddley Walker, which "left [him] in a place where there was further action pending and this further action was waiting for the element that would precipitate it into the time and place of its own story." That element arrived when his daughter Esmé and her husband Moti took him to the ruined stronghold of Montfort in Galilee, built in the 12th century by the knights of the Teutonic Order of Saint Mary and enlarged by them in the 13th century.

In Mr. Hoban's words: "The look of the stars burning and flickering over Montfort, those three stars between the Virgin and the Lion with their upward swing like the curve of a scythe, the stare into the darkness, the hooded eagleness of the stronghold high over the gorge, the paling into dawn of its gathered flaunt and power precipitated Pilgermann into his time and place and me into a place I hadn't even known was there."

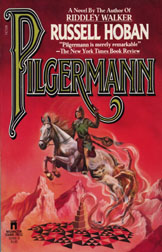

There are two book covers shown on this page; the one above left is the original hardback which depicts the pattern Pilgermann designs in Antioch. The other, shown below right, appears to be an attempt to market the book to the sword-and-sorcery market (one can only imagine how successful that must have been); it features a cover painting by fantasy artist Rowena!

REVIEW QUOTES:

"What we have here--pirates, seductive pigs and violent battles to the contrary--is not so much a tale of adventure as a meditation on history, loss and grief, a dark treatise on the mysterious nature of things...a network of small interlocking essays on matters no less significant than mutability and mortality...merely remarkable."

--Joel Cannaroe, front page, The New York Times Book Review

"Pilgermann does live, both as a character in a vivid moment of the historical past and as a living questing spirit. Hoban successfully creates a pilgrim who once traveled and who has not stopped. His novel is not an easy read, only a fascinating and rewarding one."

--Paul Gray, Time

"A novel that is both Riddley Walker'scomplement and mirror image....a direct approach to 'the living heart of mystery.'"

--Harper's

OTHER REVIEWS AND ARTICLES:

Evelyn C. Leeper's review of Pilgermann.

MEMORABLE LINES AND PASSAGES:

A story is what remains when you leave out most of the action. (p.38)

'Why are you weeping?' said Bembel Rudzuk.

'I am suffering from an attack of history,' I said.

'It will pass,' said Bembel Rudzuk. (p. 117)

One assumes that the world simply is and is and is but it isn't, it is like music that we hear a moment at a time and put together in our heads. But this music, unlike other music, cannot be performed again. (p.99)

What is called time passes and yet all time is present; one has only to turn one's head to see the happening of all things...(p. 62)

When one is a child, when one is young, when one has not yet reached the age of recognition, one thinks that the world is strong, that the strength of God is endless and unchanging. But after the thing has happened--whatever that thing might be--that brings recognition, then one knows irrevocably how very fragile is the world, how very, very fragile; it is like one of those ideas that one has in dreams: so clear and so self-explaining are they that we make no special effort to remember. Then of course they vanish as we wake and there is nothing there but the awareness that something very clear has altogether vanished. (p. 62)

There is a mystery that even God cannot fathom, nor can he give the law of it on two stone tablets. He cannot speak what there are no words for; he needs divers to dive into it; he needs wrestlers to wrestle with it, singers to sing it, lovers to love it. He cannot deal with it alone, he must find helpers, and for this does he blind some and maim others. (p.201)

Sometimes I don't know anything at all for large spaces; sometimes I know many things all in the same place. My perceptions are uneven, my understanding patchy but I have action; I go. I can't tell this as a story because it isn't a story; a story is what remains when you leave out most of the action; a story is a coherent sequence of picture cards: One: Samson in the vineyards of Timnah; Two: the lion comes roaring at Samson; Three: Samson tears the lion apart. That's a story but actually the main part of the action may have been that there was butterfly in Samson's field of vision the whole time. The picture cards don't show the butterfly because if they did they would have to explain it. But you can't explain the butterfly. (p.38)

Mortal life is a difficult proposition because hardly anything can be experienced as what it actually is; everything is time-distorted. In childhood we wait for things that seem too long in coming, we wait for treats, for presents, for festivals and holidays, we wait for growing up. There is so much waiting that suddenly childhood itself is gone with all that was being waited for. As grown-ups we find ourselves pitched headlong down a steep and slippery slide with everything hurtling towards us at great speed; some things smash us full in the face, others streak past half-glimpsed or unseen; everything has happened before we were ready for it. Only after the hurly-burly of mortal life is over can one have a really good look at what has happened; unburdened by choice and unthreatened by consequences one is able to sort through the half-glimpses of a lifetime and find perhaps one or two workable fragments of recognition. (p.183)

The pirate captain was delighted to find that I was a eunuch in good condition; he made that gesture of kissing the fingers made by all vendors who reckon that they have something especially fine to sell...It occurred to me that I might be bought for harem duty and I felt a little stir of pleasure; orchards are pleasant even if one can't climb the trees. (p. 105)

I don't know what I am now. A whispering out of the dust. Dried blood on a sword and the sword has crumbled into rust and the wind has blown the rust away but still I am, still I am of the world, still I have something to say, how could it be otherwise, the action never stops, it only changes, the ringing of steel is sung in the stillness of the stone. (p. 11)

Back to The Head of Orpheus: a Russell Hoban Reference Page (home page).

Russell Hoban's other novels and collections: